Mobile Money at Sixteen (Part 2/3): What We Got Wrong: Lessons from Mobile Money's Journey

- Kofi Owusu-Nhyira

- Dec 21, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 15

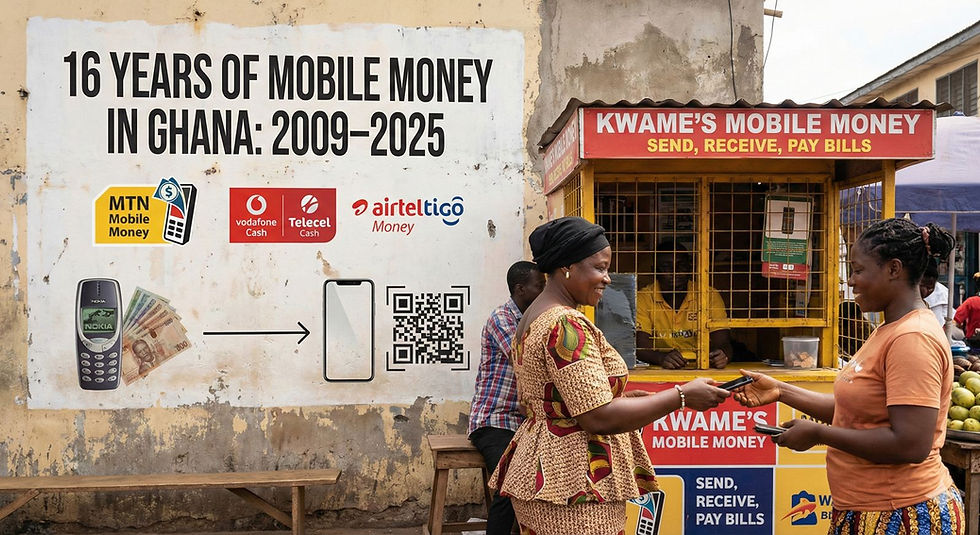

In Part 1, I explored how the adoption of mobile money surprised everyone. It was human behavior, not just technology, that drove its scale. However, success often hides the missteps we took along the way.

This is Part 2: what we got wrong.

The Blind Spots Behind the Success

Cash Was Supposed to Decline. It Did Not.

Mobile money digitized the movement of value, but not its final state. Cash-in and cash-out still dominate transaction types. Most merchants, transport operators, and traders treat cash as the default endpoint.

The informal economy absorbed mobile money into its own logic, rather than the other way around.

Merchant Payments Were Expected to Boom. They Did Not.

Despite the rollout of GhQR and the expansion of POS and merchant wallet solutions, merchant payments remain a small share of total mobile money volumes. The reasons are largely behavioral and economic:

Merchants prefer cash for flexibility and privacy.

Consumers want to avoid transaction fees.

Many traders are cautious about digital records in a tax-sensitive environment.

Thin business margins make fees feel punitive rather than enabling.

Merchant acceptance has always been less about technology and more about incentives, margins, and trust.

Fraud Outpaced Protection Systems

By around 2018, fraud patterns shifted from simple social-engineering tactics to more sophisticated schemes, including SIM-swap fraud, agent impersonation, insider collusion, and rapid cross-network value movement. The features that drove inclusion—speed, simplicity, and human intermediaries—also created new vulnerabilities.

These issues arose not from poor design but because adoption outpaced the maturity of fraud management and cybersecurity frameworks.

Agent Liquidity Became a Systemic Weak Point

By 2024, nearly half of registered agents were inactive. This wasn't due to lack of demand but rather float constraints and limited access to affordable working capital. The system placed national infrastructure responsibilities on agents with thin capital buffers and poorly understood business risks.

A Bigger Misread: What Fintech Was Supposed to Deliver

The promise of mobile money and fintech was not just wider access but also financial deepening:

Increased savings

Stronger domestic resource mobilization

More accessible and appropriately priced credit for MSMEs

Data trails to support responsible lending

Ghana delivered access at scale but has yet to achieve depth. We built access rails but did not build value-retention rails.

Policy Intent and Market Reality Drifted Apart

For over a decade, Ghana's digital finance policy assumed users would gradually migrate toward more formal app-based and bank-like behaviors. Policymakers believed that:

Apps would replace USSD as smartphones became more common.

Increased digital access would lead to more formal financial behavior.

Merchants would rapidly digitize and accept electronic payments.

Transaction data would unlock credit for MSMEs and households.

Digital usage would naturally lead to savings and asset accumulation.

Cash usage would fall as digital rails expanded.

None of these shifts occurred at the expected pace. The problem was not the aspiration itself but that these assumptions were based on imported models rather than Ghanaian reality.

Evidence from the Bank of Ghana, GSMA, and other regional assessments shows a consistent pattern across African mobile money markets: users digitize the movement of value, not its storage. Digital payments do not automatically formalize underlying financial behavior.

In Ghana specifically, over 85 percent of mobile money transactions remain USSD-based rather than app-based. Cash-in and cash-out account for the majority of usage, merchant payments are a small fraction of total transaction volumes, and only a subset of users maintain meaningful wallet balances. Credit models built purely on mobile money data have not scaled.

Digital rails did not automatically reshape economic behavior; they amplified existing behaviors.

What Actually Drove Scale: Six Behavioral Fundamentals

Mobile money grew because it aligned with six core features of Ghanaian financial life:

Trust – rooted in human agents rather than distant institutions.

Proximity – agent kiosks and tables are closer than branches and open longer.

Informality – cash-flow cycles mirror informal work and trade.

Liquidity – immediate access to convert digital value to cash.

Social Networks – family obligations and remittances as primary use cases.

Convenience – simple, menu-driven USSD flows rather than complex apps.

These are not cultural quirks; they are part of the economic infrastructure of Ghana's financial system. Any reform that ignores them risks repeating the gap between policy design and lived reality.

Regulation Evolved, But Integration Remains Incomplete

Ghana's regulatory institutions did not stand still. The Payment Systems and Services Act, 2019 (Act 987) brought much-needed structure. It defined clear license categories, consolidated KYC expectations, and clarified safeguarding obligations. From 2022, the Bank of Ghana's Regulatory and Innovation Sandbox created controlled environments for testing alternative approaches to KYC, digital lending, and API-driven models.

Despite this progress, regulation, innovation, and user behavior still operate on partially separate tracks:

Policy has provided structural clarity but often based on top-down assumptions about how users "should" behave.

Innovation has produced rapid payment scale but relatively shallow financial depth.

Users continue to navigate the system with liquidity-first logic, multi-wallet improvisation, and a preference for cash endpoints.

The next phase requires these three lanes to converge, grounded in behavioral truth, economic structure, and realistic incentives.

These misalignments weren't failures; they were learning opportunities. They point directly to what Ghana's next digital finance chapter must prioritize.

In Part 3 (final), I'll share three non-negotiable lessons from mobile money's sixteen-year journey and what "Digital Finance 2.0" must confront.

Comments