Mobile Money at Sixteen (part 3/3): From Access to Depth

- Kofi Owusu-Nhyira

- Jan 12

- 4 min read

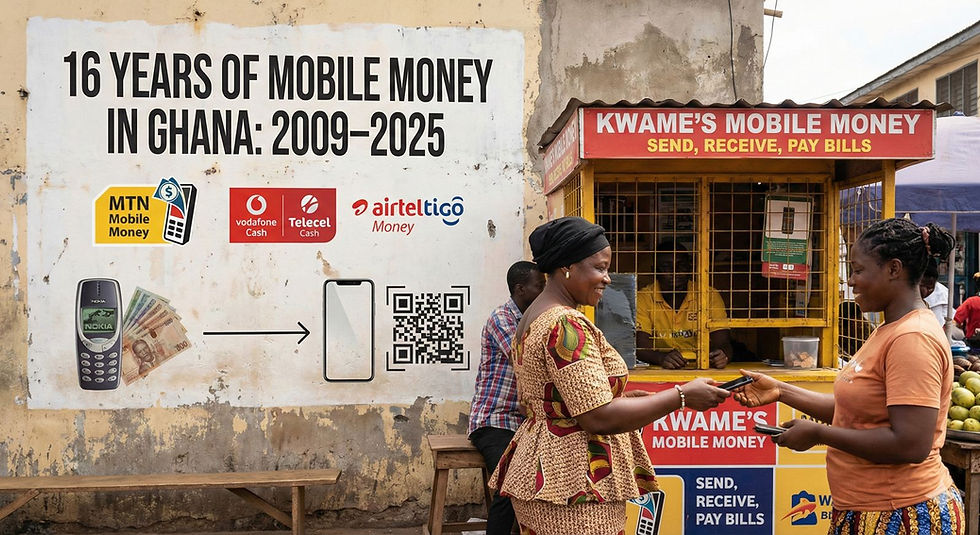

Parts 1 and 2 examined mobile money's sixteen-year journey: how adoption actually happened (not as policy predicted), and where assumptions diverged from reality.

This is Part 3: the lessons learned, and the work still ahead.

Lessons for Ghana's Next Digital Finance Chapter

Ghana now stands at the threshold of a new digital finance era, characterised by digital public infrastructure for identity, payments, and data, instant interoperable payment systems, API-based integration between banks, telcos, and fintechs, AI-driven risk models and credit scoring, rising cyber and fraud risks, and AfCFTA-enabled cross-border payments and digital trade.

Mobile money's sixteen-year journey offers three non-negotiable lessons for this next chapter.

Lesson 1: Build for behaviour, not aspiration

Digital finance succeeds when it reflects how people actually manage money, not aspirational models.

Across African markets, research by GSMA, FSD Africa, and multilateral institutions consistently shows that users digitise movement more readily than they digitise storage, and that liquidity management takes precedence over formalisation.

In Ghana, USSD remains dominant for mobile money use, cash-in and cash-out remain the main transaction categories, merchant acceptance is still modest, and average wallet balances remain low. These behaviors are structural, not transitional. Policy must therefore begin with the realities of a largely informal, liquidity-constrained economy marked by irregular incomes, interpersonal trust, fragile savings, and high perceived risk.

People adopt what fits their lives, not what fits policy blueprints.

Lesson 2: Strengthen human infrastructure

Ghana's digital finance system is built on an analogue backbone: the agent network. There are roughly 896,000 registered agents, with around 411,000 active. Liquidity shortages remain the primary cause of agent inactivity. Agents still handle the majority of cash-in and cash-out flows and perform functions similar to micro-branches rather than simple retail outlets.

Agents are the public interface of digital finance. They are the onboarding layer, the trust layer, the dispute resolution layer, and the liquidity layer. A digital ecosystem cannot be stronger than its weakest human node.

The next phase must therefore invest in working-capital and liquidity facilities for agents, more transparent and predictable settlement cycles, liquidity insurance or guarantee schemes at ecosystem level, agent-level AML/CFT, fraud, and KYC capacity building, and tiered, risk-based compliance obligations that recognize agent realities.

No digital public infrastructure will succeed if the human infrastructure beneath it collapses.

Lesson 3: Match digital innovation to economic reality

Digital rails can move value at high speed, but economic structure determines what users can actually do with that value.

Mobile money successfully digitised payments, yet Ghana has not fully realised the second half of the fintech promise: financial deepening.

Payments alone cannot deliver durable savings, credit at scale, MSME working capital, agricultural finance, insurance uptake, asset accumulation, or long-term financial resilience.

These outcomes require deeper enabling systems: interoperable, risk-based data exchange that allows supervised entities to leverage transaction histories securely and fairly, modernized credit infrastructure including responsive collateral registries and recognition of movable assets, robust identity rails with Ghana Card and digital address data integrated across onboarding and risk management, fair standardized API access so banks, telcos, and fintechs can innovate without bilateral bottlenecks, targeted merchant digitization incentives addressing fee structures and thin margins, capital access for agents and MSMEs recognizing working capital as a systemic constraint, and real-time fraud intelligence systems with cross-provider collaboration.

Payments move money. Financial deepening keeps money in the system and puts it to productive use.

What Comes Next: From Access to Depth

Alignment with behavioural reality, not technical sophistication, remains mobile money's most important policy lesson.

As Ghana advances AI-driven lending models, digital-ID enabled onboarding, central bank digital currency pilots, open-API frameworks, fintech passporting, and AfCFTA-aligned payment systems, it faces the same strategic choice that operators faced in 2009: Design for the market that exists, or for the market we wish existed.

Mobile money has already given us the answer. It also exposed the unfinished work.

Ghana has achieved something remarkable: near-universal access to digital payments and one of the fastest adoption curves on the continent. The deeper transformation, however, remains incomplete. The next chapter demands that we confront the structural issues that were previously deferred because they were harder, slower, or less commercially attractive.

The work still ahead

Strengthening human infrastructure: Agent liquidity remains the most significant operational constraint. Without addressing working capital access, settlement cycles, and agent economics, any future digital infrastructure will face the same bottleneck.

Building depth, not just access: Wallet balances remain shallow. Without value retention mechanisms, transaction data stays thin and households remain financially fragile. This requires interoperable savings tools, credit infrastructure that recognizes informal assets, and products designed for irregular income patterns.

Expanding interoperability beyond payments: Ghana solved wallet-to-wallet interoperability in 2018. Critical next layers remain underdeveloped: merchant interoperability, API interoperability, cross-border interoperability, and risk-based data exchange across the ecosystem.

Aligning incentives for merchant digitization: Despite GhQR and POS growth, micro-merchants still prefer cash due to fee sensitivity, settlement cycles, and working capital dynamics. Digitization requires addressing these structural constraints, not just deploying more terminals.

Creating regulatory clarity beyond payments: Act 987 provides clear frameworks for payments, but digital credit, savings-focused fintechs, and asset platforms still operate in grey areas. This uncertainty pushes founders toward transactional models where rules are predictable, limiting depth-focused innovation.

From Mobile Money to Digital Finance 2.0

Mobile money was Ghana's great experiment in access. It succeeded because it respected behavioral reality rather than imposing aspirational models.

The next phase, Digital Finance 2.0, must be Ghana's deliberate project in depth. Not just moving money, but retaining it. Not just transactions, but financial resilience. Not just inclusion, but transformation.

This requires confronting the hard problems we deferred when building for access: agent economics, savings mobilization, credit architecture, merchant incentives, data interoperability, and patient capital.

These challenges are not primarily technical. They are structural, behavioral, and economic. And addressing them will require the same ecosystem collaboration that built mobile money: operators learning from users, regulators responding to reality, and founders building for actual needs rather than imagined markets.

Sixteen years taught us how to reach millions. The next sixteen must teach us how to serve them deeply.

Because access without depth is not financial inclusion. It is digital infrastructure that touches lives without transforming them.

And Ghana is capable of more.

Comments